Pengertian Tenses

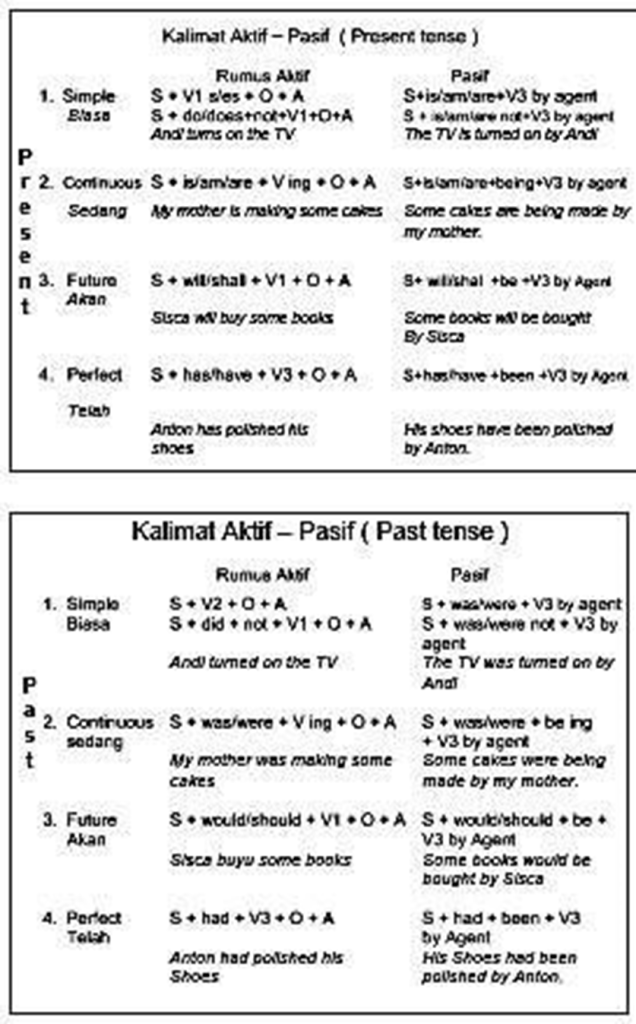

Tenses merupakan suatu kata kerja dalam bahasa inggris yang bertujuan untuk menunjukan waktu (sekarang, masa depan, atau masa lalu) serta terjadinya suatu perbuatan atau peristiwa. Tenses sendiri dibagi menjadi 3 bagian besar, yaitu: Past, Present, Future. Dan dalam bahasa indonesianya bermakna Dulu, Kini, dan Nanti. Tenses sendiri di bagi menjadi 16 bentuk. 4 tense ada dalam past. 4 tense

dalam present dan 8 tense lagi ada dalam future.

Bentuk, Pengertian, Rumus, dan Contoh Tenses

a. Present

Present merupakan suatu kata kerja yang bisa dibilang menunjukan waktu

lebih tepatnya saat ini, present dibagi menjadi 4 tenses, yaitu present tense, present

continuous tense, present perfect tense dan present perfect continuous tense. Present tense adalah suatu bentuk kata kerja yang digunakan untuk menyatakan fakta, kebiasaan, kejadian, kegiatan, aktivitas dan sebagainya yang terjadi pada saat ini. Present Tense juga digunakan untuk menyatakan suatu Fakta,

atau sesuatu yang tejadi berulang-ulang dimasa KINI. Bentuk kata kerja ini paling sering diguanakan dalam bahasa Inggris

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + V1 (s/es)

Negatif : S + DO/DOES + NOT +V1

Tanya : DO/DOES + S + V1

Contoh :

(+) he drinks milk

(- ) he doesn‘t drink milk

(?) does he drink milk ?

Present Continuous Tense

Present continuous tense adalah suatu bentuk kata kerja yang digunakan

untuk menyatakan, mengatakan, membicarakan aksi yang sedang berlangsung

sekarang (present) atau rencana di masa depan (future). Karena dapat diguanakan

dalam present atau future. Tense ini sering diiringi adverb of time untuk memperjelasnya.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + Tobe +Ving

Negatif : S +Tobe +Not + Ving

Tanya : Tobe + S + Ving

Contoh :

(+) We are studying now

(- ) We aren‘t studying now

(?) Are you studying now ?

Present Perfect Tense

Present perfect adalah suatu bentuk kerja yang digunakan untuk menyatakan

suatu perbuatan atau peristiwa yang telah dikerjakan dan masih berkaitan dengan

masa sekarang

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + Have/has + V3

Negative : S + Have/has Not + V3

Tanya : Have/has + S + V3

Contoh:

(+) I have lived here for 2 years

(- ) I haven‘t lived here 2 years

(?) Have you livedhere 2 years ?

Present perfect continuous tense

Present perfect continuous tense suatu bentuk kata kerja yang diguanakan

untuk menyatakan sebuah peristiwa atau kejadian yang baru saja selesai .

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + Have/has + been + Ving

Negative : S + have/has +not + been + Ving

Tanya : have/has+ S + been + Ving

Contoh :

(+) She has been eating

(- ) She has not beeneating

(?) Has She beeneating ?

b. Past

Past merupakan suatu kata kerja yang bisa dibilang menunjukan waktu lebih tepatnya dahulu/yang sudah lampau, past dibagi menjadi 4 tense, yaitu past tense, past continuous tense, past perfecet tense dan past perfect continuous tense.

Past tense

Past tense merupakan tense yang digunakan untuk menyatakan peristiwa yang telah ―Lampau‖. Lampau disini tak harus sudah terlalu lama, yang penting sudah berlalu, sudah lewat. Itulah penekanannya. Mungkin kemarin, satu jam lalu, 1 tahun yang lalu, 1 abad yang lalu, dan sebagainya.

Rumusnya :

Positif : S + V2

Negative : S + did + not + V1 Tanya

: Did + S + V1

Contoh:

(+) He bought a pair of shoes yesterday

(- ) He didn‘t buy a pair of shoes yesterday

(?) Did he buy a pair of shoes yesterday ?

Past continuous tense

Past continuous tense merupaka tense yang digunakan untuk

menyatakan peristiwa yang sedang terjadi juga, tetapi sedang terjadi sekarangg,

melainkan sedang terjadi tetapi dulu, tetapi sudah lewat.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + was/were +Ving

Negatif : S + was/were + not + Ving

Tanya : Was/were + S + Ving

Contoh :

(+) He was cooking

(- ) He was notcooking

(?) Was hecooking ?

Past perfect tense

Past perfect tense adalah bentuk waktu yang digunakan untuk menunjukan,

menyatakaan sesuatu yang telah selesai dilakukan pada saat itu (dimasa

lampau/waktu yang telah lalu).

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + Had + V3

Negative: S + had + not + V3

Tanya : had + S + V3

Contohnya :

(+) My parents had already eaten by the time i got home

(- ) Sam had not left when we got there

(?) When your son was in the junior high school, had you lived there ?

Past perfect continuous tense

past perfect continuous tense adalah bentuk yang digunakan untuk

menyatakan hal atau peristiwa yang sesuatu yang telah dan sedang terjadi dimasa

lampau.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + had + been + Ving

Negative : S + Had + not + been + Ving

Tanya : had + S + been + Ving

Contohnya

(+) She had been reading a

novel

(- ) She had not reading

a novel

(?) Had She been reading a novel ?

c. Future

future merupakan suatu kata kerja yang bisa dibilang menunjukan waktu lebih

tepatnya Nanti/yang belum terjadi, dalam future dibagi menjadi 8 bentuk, yaitu :

future tense, future continuous tense, future perfect tense, future perfect continuous

tense, past future tense, past future continuous tense, past future perfect tense, dan

past future perfecet continuous tense.

Future tense

Future tense bentuk waktu yang digunakan untuk untuk menyatakan

perbuatan atau peristiwa yang akan Terjadi. Future tense adalah tentang Nanti.

Sesuatu arti katanya Future yaitu masa depan

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + will + V1

Negative: S + will + not + V1

Tanya : Will + S + V1

Contoh :

(+) He wiil go to Bandung tomorrow

(- ) He will not go to Bandung tomorrow

(?) Will he go to Bandung tomorrow ?

Future continuous tense

Future continuous tense bentuk waktu yang digunakan untuk menyatakan

suatu peristiwa yang akan Sedang Terjadi atau akan sedang dilakukan di waktu

tertentu di masa yang akan datang juga sebagaimana Present Continuous Tense,

tetapi bedanya dalam Future Continuous Tense maka ―Sedang‖ nya itu bukan

sekarang melainkan besok, akan datang, nanti.

Rumusnya :

Positif : S + will + be + Ving

Negatif : S + will + not + be + Ving

Tanya : Will + S + be + Ving

Contoh :

(+) She will be reading at 8 p.m

(- ) She will not be reading at 8

p.m (?) Will she be reading at 8

p.m ?

Future perfect tense

Future perfect tense bentuk waktu yang digunakan untuk menyatakan

sesuatu yang akan selesai di masa depan yang sudah mulai di masa lalu.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + will + have + V3

Negative : S + will + not + have +V3

Tanya : will + S + have + V3

Contoh:

(+) Dika will have rented my house next month

(- ) Dika will not have rented my house next month

(?) Will Dika have rented my house next month ?

Future perfect continuous tense

Future perfect continuous tense adalah suatu bentuk kerja yang digunakan

untuk menyatakan bahwa suatu aksi akan sudah berlangsung selama sekian lama

pada titik waktu tertentu di masa depan atau peristiwa yang akan, telah dan masih

berlangung di masa datang.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + will + have + been + Ving

Negative : S + will + not + have + been + ving

Tanya : will + S + have + been + Ving

Contoh :

(+) The cat will have been sleeping long

(- ) The cat won‘t have been sleeping

long (?) Will the cat have been

sleeping long ?

Past future tense

Past future tense adalah suatu bentuk kata kerja yang digunakan untuk

menyatakan peristiwa akan dilakukan tetapi di masa lampau bukan saat ini.

Rumusnya :

Positif : S + would + V1

Negative : S + would + not + V1

Tanya : would + S + V1

Contoh :

(+) You would work

(- ) You would not work

(?) would you wrok ?

Past future continuous tense

Past future continuous tense adalah bentuk waktu yang digunakan untuk

menyatakan peristiwa yang akan sedang dilakukan, di waktu tertentu di masa yang

akan datang.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + would + be + Ving

Negative: S + would + not + be + Ving

Tanya : Would + S + be + Ving

Contoh:

(+) I would be taekwondo training at 6 yesterday.

(- ) I would not be taekwondo training at 6 yesterday.

(?) Would you be taekwondo training at 6 yesterday ?

Past future perfect tense

Past future perfect tense merupakan tense yang digunakan untuk menyatakan sesuatu yang Sudah terjadi, tetapi AKAN namun posisinya pasti sudah berlalu.

Rumusnya:

Positif : S + would + have + V3

Negative : S + would + not + have + V3

Tanya : would + S + have + V3

Contoh :

(+) They would have driven home

(- ) They would not have driven home

(?) Would they have driven home ?

Past future perfect continuous tense

Past future perfect continuous tense merupakan tense yang digunakan untuk

menyatakan peristiwa yang akan, telah dan masih berlangung di masa yang lalu,

masa lampau. Past Future Perfect Continuous Tense mengenai peristiwa atau hal

yang akan telah sedang terjadi di masa lampau.

Rumusnya :

Positif : S + would + have + been + Ving

Negative : S + would + not + have + been + Ving

Tanya : would + S + have + been + Ving

Contoh :

(+) She would have been working there for 1 year

(- ) She would not have been working there for 1 year

(? ) Would she have been working there for 1 year?

d. DEGREE OF COMPARISON

degree of comparison membahas mengenai perbandingan bisa pada

adjective (kata sifat) maupun adverb (kata keterangan). Artikel ini membahas

mengenai adjective degree of comparison. Perbandingan pada adjective

menunjukan seberapa besar, kecil, atau banyak kata benda atau kata ganti dalam

sebuah kalimat.

- Jenis-jenis degree of comparison.

Terdapat tiga tingkat perbandingan yaitu positive degree, comparative degree, dan superlative degree.

Positive degree

Positive degree merupakan bentuk adjective secara sederhana dan tidak membandingkan suatu hal.

I am handsome. (Sayatampan.) The girl is tall.(Gadis itu tinggi.)

Their family is bad. (Keluarga mereka buruk.)

Comparative degree (lebih (more)) Membandingkan dua orang atau hal.

I am more handsome than Roni. (Saya lebih tampan dari Roni.)

The girl is taller than her mother. (Gadis itu lebih tinggi dari ibunya.)

Their family is worse than our family. (Keluarga mereka lebih buruk dari keluarga kita.)

Superlative degree (paling/ ter- (most))

Menunjukan ‗yang paling‘, superlative degree ini digunakan ketika terdapat lebih dari dua hal yang dibandingkan. Untuk bentuk dari superlative degree harus diawali dengan ‗the‘ sebelum kata sifatnya.

I am the most handsome student in the class. (Saya adalah siswa

paling tampan di kelas.)

The girl is the tallest girl in the competition. (Gadis itu adalah

gadis tertinggi di kompetisi)

Their family is the worst family in the world. (Keluarga mereka

adalah keluarga terburuk di dunia.) - Bentuk-bentuk degree of comparison.

Terdapat bentuk-bentuk yang berbeda untuk setiap jenisnya, untuk positive

degree bentuknya tetap adjective sederhana, seperti, handsome tall, bad, clever dan

lain sebagainya. Sedangkan untuk comparative dan superlative degree bentuknya

lebih variatif.

Untuk kata sifat yang bersuku kata satu atau dua, pada comparative degree

tambahkan ‗+er‘ pada setiap kata sifatnya, sedangkan pada superlative

tambakan ‗est‘.

Untuk kata sifat yang bersuku kata lebih dari dua pada comparative degree

tambahan ‗more‘ pada setiap kata sifatnya, sedangkan pada superlative

tambahan ‗the most‘.

Untuk kata sifat yang berakhiran ‗e‘ bersuku kata satu/dua pada comparative

degree tambahan ‗+‘ setiap kata sifatnya, sedangkan pada superlative

tambahan ‗st‘

Untuk kata sifat yang berakhiran ‗y‘ bersuku kata satu atau dua, pada

comparative degree hapuskan huruf akhir ‗y‘ tambahkan ‗er‘ pada setiap kata

sifatnya, sedangkan pada superlative tambahankan ‗est‘.

e. PREPOTITION

Prepositions are words which link nouns, pronouns and phrases to other words

in a sentence

Prepositions usually describe the position of something, the time when

something happens and the way in which something is done, although the

prepositions “of,” “to,” and “for” have some separate functions.

Prepositions can sometimes be used to end sentences. For example, “What

did you put that there for?” Example 2: “A pen is a device to write with”.

The table below shows some examples of how prepositions are used in

sentences

KALIMAT PASIF

CLAUSES

In language, a phrase is the smallest grammatical unit that can express an incomplete proposition.[1] A typical clause consists of a subject and a predicate,[2] the latter typically a verb phrase, a verb with any objects and other modifiers. However, the subject is sometimes not said or explicit, often the case in null-subject languages if the subject is retrievable from context, but it sometimes also occurs in other languages such as English (as in imperative sentences and non-finite clauses).

A simple sentence usually consists of a single finite clause with a finite verb that is independent. More complex sentences may contain multiple clauses. Main clauses (matrix clauses, independent clauses) are those that can stand alone as a sentence. Subordinate clauses (embedded clauses, dependent clauses) are those that would be awkward or incomplete if they were alone.

In language, a phrase is the smallest grammatical unit that can express an incomplete proposition.[1] A typical clause consists of a subject and a predicate,[2] the latter typically a verb phrase, a verb with any objects and other modifiers. However, the subject is sometimes not said or explicit, often the case in null-subject languages if the subject is retrievable from context, but it sometimes also occurs in other languages such as English (as in imperative sentences and non-finite clauses).

A simple sentence usually consists of a single finite clause with a finite verb that is independent. More complex sentences may contain multiple clauses. Main clauses (matrix clauses, independent clauses) are those that can stand alone as a sentence. Subordinate clauses (embedded clauses, dependent clauses) are those that would be awkward or incomplete if they were alone.

Two major distinctions

A primary division for the discussion of clauses is the distinction between main clauses (i.e. matrix clauses, independent clauses) and subordinate clauses (i.e. embedded clauses, dependent clauses).[3] A main clause can stand alone, i.e. it can constitute a complete sentence by itself. A subordinate clause (i.e. embedded clause), in contrast, is reliant on the appearance of a main clause; it depends on the main clause and is therefore a dependent clause, whereas the main clause is an independent clause.

A second major distinction concerns the difference between finite and non-finite clauses. A finite clause contains a structurally central finite verb, whereas the structurally central word of a non-finite clause is often a non-finite verb. Traditional grammar focuses on finite clauses, the awareness of non-finite clauses having arisen much later in connection with the modern study of syntax. The discussion here also focuses on finite clauses, although some aspects of non-finite clauses are considered further below.

Argument clauses

A clause that functions as the argument of a given predicate is known as an argument clause. Argument clauses can appear as subjects, as objects, and as obliques. They can also modify a noun predicate, in which case they are known as content clauses.

- That they actually helped was really appreciated. – SV-clause functioning as the subject argument

- They mentioned that they had actually helped. – SV-clause functioning as the object argument

- What he said was ridiculous. – Wh-clause functioning as the subject argument We know what he said. – Wh-clause functioning as an object argument

- He talked about what he had said. – Wh-clause functioning as an oblique object argument

The following examples illustrate argument clauses that provide the content of a noun. Such argument clauses are content clauses:

- the claim that he was going to change it – Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause)

- the claim that he expressed – Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun

- the idea that we should alter the law – Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause)

- the idea that came up – Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun The content clauses like these in the a-sentences are arguments. Relative clauses introduced by the relative pronoun that as in the b- clauses here have an outward appearance that is closely similar to that of content clauses. The relative clauses are adjuncts, however, not arguments.

Adjunct clauses

Adjunct clauses are embedded clauses that modify an entire predicate-argument structure. All clause types (SV-, verb first, wh-) can function as adjuncts, although the stereotypical adjunct clause is SV and introduced by a subordinator (i.e. subordinate conjunction, e.g. after, because, before, when, etc.), e.g.

- Fred arrived before you did. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

- After Fred arrived, the party started. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

- Susan skipped the meal because she is fasting. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

These adjunct clauses modify the entire matrix clause. Thus before you did in the first example modifies the matrix clause Fred arrived. Adjunct clauses can also modify a nominal predicate. The typical instance of this type of adjunct is a relative clause, e.g.

- We like the music that you brought. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun music

- The people who brought music were singing loudly. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun people

- They are waiting for some food that will not come. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun food

Predicative clauses

An embedded clause can also function as a predicative expression. That is, it can form (part of) the predicate of a greater clause.

- That was when they laughed. – Predicative SV-clause, i.e. a clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

- He became what he always wanted to be. – Predicative wh-clause, i.e. wh- clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

- These predicative clauses are functioning just like other predicative expressions,

- e.g. predicative adjectives (That was good) and predicative nominals (That was the truth). They form the matrix predicate together with the copula.

MODALS

A modal verb is a type of verb that is used to indicate modality – that is: likelihood, ability, permission, request, capacity, suggestions, order and obligation, and advice etc. They always take v1 form with them.[1] Examples include the English verbs can/could, may/might, must, will/would and shall/should. In English and other Germanic languages, modal verbs are often distinguished as a class based on certain grammatical properties.

Function

A modal auxiliary verb gives information about the function of the main

verb that it governs. Modals have a wide variety of communicative functions, but these functions can generally be related to a scale ranging from possibility (“may”) to necessity (“must”), in terms of one of the following types of modality:

epistemic modality, concerned with the theoretical possibility of propositions being true or not true (including likelihood and certainty) deontic modality, concerned with possibility and necessity in terms of freedom to act (including permission and duty)

dynamic modality,[2] which may be distinguished from deontic modality in that, with dynamic modality, the conditioning factors are internal – the subject’s own ability or willingness to act[3]

The following sentences illustrate epistemic and deontic uses of the English modal verb must:

epistemic: You must be starving. (“It is necessarily the case that you are starving.”)

deontic: You must leave now. (“You are required to leave now.”)

An ambiguous case is You must speak Spanish. The primary meaning would be the deontic meaning (“You are required to speak Spanish.”) but this may be intended epistemically (“It is surely the case that you speak Spanish.”) Epistemic

modals can be analyzed as raising verbs, while deontic modals can be analyzed as control verbs.

Epistemic usages of modals tend to develop from deontic usages.[4] For example, the inferred certainty sense of English must developed after the strong obligation sense; the probabilistic sense of should developed after the weak obligation sense; and the possibility senses of may and can developed later than the permission or ability sense. Two typical sequences of evolution of modal meanings are:

internal mental ability → internal ability → root possibility (internal or

external ability) → permission and epistemic possibility obligation →

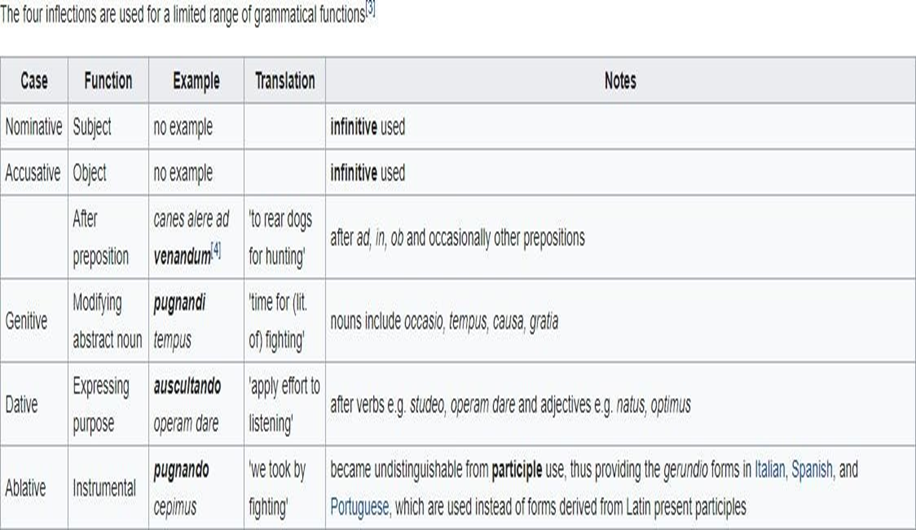

probability GERUNDS

A gerund (/ˈdʒɛrənd, -ʌnd/[1] abbreviated ger) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages, most often, but not exclusively, one that functions as a noun. In English it is a type of verbal noun, one that retains properties of a verb, such as being modifiable by an adverb and being able to take a direct object. The term “-ing form” is often used in English to refer to the gerund specifically. Traditional grammar made a distinction within -ing forms between present participles and gerunds, a distinction that is not observed in such modern, linguistically informed grammars as A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language and The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.

These functions could be fulfilled by other abstract nouns derived from verbs such as vẽnãtiõ ‘hunting’. Gerunds are distinct in two ways.

Every Latin verb can regularly form a gerund

A gerund may function syntactically in the same way as a finite verb. Typically the gerund of a finite verb may be followed by a direct object e.g. ad discernendum vocis verbis figuras ‘for discerning figures of speech’, hominem investigando opera dabo ‘I will devote effort to investigating the man’.

However, this was a rare construction. Writers generally preferred the gerundive construction e.g. res evertendae reipublicae ‘matters concerning the overthrow of the state’ (literally ‘of the state being overthrown’).

When people first wrote grammars of languages such as English, and based them on works of Latin grammar, they adopted the term gerund to label non-finite verb forms with these two properties.

TYPES

Personal

| English personal pronouns[2]:52 | ||

| Perso n | Number | Case |

| Subjec t | Object |

| First | Singular | I | me |

| Plural | we | us | |

| Secon d | Singular | you | |

| Plural | |||

| Third | Singular | he | him |

| she | her | ||

| it | |||

| they | them | ||

| Plural | they | them |

Personal pronouns may be classified by person, number, gender and case. English has three persons (first, second and third) and two numbers (singular and plural); in the third person singular there are also distinct pronoun forms for male, female and neuter gender. Principal forms are shown in the adjacent table (see also English personal pronouns).

English personal pronouns have two cases, subject and object. Subject pronouns are used in subject position (I like to eat chips, but shedoes not). Object pronouns are used for the object of a verb or preposition (John likes me but not her).

Other distinct forms found in some languages include:

- Second person informal and formal pronouns (the T-V distinction), like tu and vous in French. There is no such distinction in standard modern English, though Elizabethan English marked the distinction with thou (singular informal) and you (plural or singular formal), and this is preserved in some dialects.

- Inclusive and exclusive first person plural pronouns, which indicate whether or not the audience is included, that is, whether “we” means

“you and I” or “they and I”. There is no such distinction in English.

- Intensive (emphatic) pronouns, which re-emphasize a noun or pronoun that has already been mentioned. English uses the same forms as the reflexive pronouns; for example: I did it myself (contrast reflexive use, I did it to myself).

- Direct and indirect object pronouns, such as le and lui in French. English uses the same form for both; for example: Mary loves him(direct object); Mary sent him a letter (indirect object).

- Prepositional pronouns, used after a preposition. English uses ordinary object pronouns here: Mary looked at him.

- Disjunctive pronouns, used in isolation or in certain other special grammatical contexts, like moi in French. No distinct forms exist in English; for example: Who does this belong to? Me.

- Strong and weak forms of certain pronouns, found in some languages such as Polish.

- Some special uses of personal pronouns include:

- Generic you, where second person pronouns are used in an indefinite sense: You can’t buy good old-fashioned bulbs these days.

- Generic they: In China they drive on the right.

- Gender non-specific uses, where a pronoun needs to be found to refer to a person whose sex is not specified. Solutions sometimes used in English include generic he and singular they.

- Dummy pronouns (expletive pronouns), used to satisfy a grammatical requirement for a noun or pronoun, but contributing nothing to meaning: It is raining..

- Resumptive pronouns, “intrusive” personal pronouns found (for example) in some relative clauses where a gap (trace) might be expected: This is the girl that I don‘t know what she said.

Reflexive and reciprocal

Main articles: Reflexive pronoun and Reciprocal pronoun

Reflexive pronouns are used when a person or thing acts on itself, for example, John cut himself. In English they all end in -self or – selvesand must refer to a noun phrase elsewhere in the same clause.

Reciprocal pronouns refer to a reciprocal relationship (each other, one another). They must refer to a noun phrase in the same clause. An example in English is: They do not like each other. In some languages, the same forms can be used as both reflexive and reciprocal pronouns.

Possessive

Main articles: Possessive and Possessive determiner

Possessive pronouns are used to indicate possession (in a broad sense). Some occur as independent noun phrases: mine, yours, hers, ours, yours, theirs. An example is: Those clothes are mine. Others act as

a determiner (adjective) and must accompany a noun: my, your, her, our, your, their, as in: I lost my wallet. (His and its can fall into either category, although its is nearly always found in the second.) Those of the second type have traditionally also been described as possessive adjectives, and in more modern terminology as possessive determiners. The term “possessive pronoun” is sometimes restricted to the first type. Both types replace possessivenoun phrases. As an example, Their crusade to capture our attention could replace The advertisers’ crusade to capture our attention.

Demonstrative

Main article: Demonstrative pronoun

Demonstrative pronouns (in English, this, that and their plurals these, those) often distinguish their targets by pointing or some other indication of position; for example, I’ll take these. They may also be anaphoric, depending on an earlier expression for context, for example, A kid actor would try to be all sweet, and who needs that?

Indefinite

Main article: Indefinite pronoun

Indefinite pronouns, the largest group of pronouns, refer to one or more unspecified persons or things. One group in English includes compounds of some-, any-, every- and no- with -thing, -one and -body, for example: Anyone can do that. Another group, including many, more, both, and most, can appear alone or followed by of. In addition,

- Distributive pronouns are used to refer to members of a group separately rather than collectively. (To each his own.)

- Negative pronouns indicate the non-existence of people or things. (Nobody thinks that.)

- Impersonal pronouns normally refer to a person, but are not specific as to first, second or third person in the way that the personal pronouns are. (One does not clean one’s own windows.)

Relative

Main article: Relative pronoun

Relative pronouns (who, whom, whose, what, which and that) refer back to people or things previously mentioned: People who smoke should quit now. They are used in relative clauses.[2]:56

Interrogative

Main article: Interrogative word

Interrogative pronouns ask which person or thing is meant. In reference to a person, one may use who (subject), whom (object) or whose (possessive); for example, Who did that? In colloquial speech, whom is generally replaced by who. English non-personal interrogative

pronouns (which and what) have only one form.

In English and many other languages (e.g. French and Czech), the sets of relative and interrogative pronouns are nearly identical. Compare English: Who is that?(interrogative) and I know the woman who came (relative). In some other languages, interrogative pronouns and indefinite pronouns are frequently identical; for example, Standard Chinese 什 么shénme means “what?” as well as “something” or “anything”.

Archaic forms

| Archaic personal pronouns[2]:52 | |||

| Perso n | Number | Case | |

| Subjec t | Object | ||

| Secon d | Singular | thou | thee |

| Plural | ye | you |

Though the personal pronouns described above are the contemporary English pronouns, older forms of modern English (as used by Shakespeare, for example) use a slightly different set of personal pronouns as shown in the table. The difference is entirely in the second person. Though one would rarely find these older forms used in literature from recent centuries, they are nevertheless considered modern.

Antecedents

The use of pronouns often involves anaphora, where the meaning of the pronoun is dependent on another referential element. The referent of the pronoun is often the same as that of a preceding (or sometimes following) noun phrase, called the antecedent of the pronoun. The following sentences give examples of particular types of pronouns used with antecedents:

- Third-person personal pronouns:

- That poor man looks as if he needs a new coat. (the noun phrase that poor man is the antecedent of he)

- Julia arrived yesterday. I met her at the station. (Julia is the antecedent of her)

- When they saw us, the lions began roaring (the lions is the antecedent of they; as it comes after the pronoun it may be called a postcedent)

- Other personal pronouns in some circumstances:

- Terry and I were hoping no-one would find us. (Terry and I is the antecedent of us)

- You and Alice can come if you like. (you and Alice is the antecedent of the second

– plural – you)

- Reflexive and reciprocal pronouns:

- Jack hurt himself. (Jack is the antecedent of himself)

- We were teasing each other. (we is the antecedent of each other)

- Relative pronouns:

- The woman who looked at you is my sister. (the woman is the antecedent of who)

Some other types, such as indefinite pronouns, are usually used without antecedents. Relative pronouns are used without antecedents in free relative clauses. Even third-person personal pronouns are sometimes used without antecedents (“unprecursed”) – this applies to special uses such as dummy pronouns and generic they, as well as cases where the referent is implied by the context.

Theoretical considerations

Pronouns (antōnymía) are listed as one of eight parts of speech in The Art of Grammar, a treatise on Greek grammar attributed to Dionysius Thrax and dating from the 2nd century BC. The pronoun is described there as “a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person.” Pronouns continued to be regarded as a part of speech in Latin grammar (the Latin term being pronomen, from which the English name – through Middle French – ultimately derives), and thus in the European tradition generally.

In more modern approaches, pronouns are less likely to be considered to be a single word class, because of the many different syntactic roles that they play, as represented by the various different types of pronouns listed in the previous sections.[4]

| Pronou n | Determiner | |

| Possessive | ours | our freedom |

| Demonstrativ e | this | this gentleman |

| Indefinite | some | some frogs |

| Negative | none | no information |

| Interrogative | which | which option |

Certain types of pronouns are often identical or similar in form to determiners with related meaning; some English examples are given in the table on the right. This observation has led some linguists, such as Paul Postal, to regard pronouns as determiners that have had their following noun or noun phrase deleted.[5] (Such patterning can even be claimed for certain personal pronouns; for example, we and you might be analyzed as determiners in phrases like we Brits and you tennis players.)

Other linguists have taken a similar view, uniting pronouns and determiners into a single class, sometimes called “determiner-pronoun”, or regarding determiners as a subclass of pronouns or vice versa. The distinction may be considered to be one of subcategorization or valency, rather like the distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs – determiners take a noun phrase complement like transitive verbs do, while pronouns do not.[6] This is consistent with the determiner phrase viewpoint, whereby a determiner, rather than the noun that follows it, is taken to be the head of the phrase.

The grammatical behavior of certain types of pronouns, and in particular their possible relationship with their antecedents, has been the focus of studies in binding, notably in the Chomskyan government and binding theory. In this context, reflexive and reciprocal pronouns (such as himself and each other) are referred to as anaphors (in a specialized restricted sense) rather than as pronominal elements.

ADJECTIVE

In linguistics, an adjective (abbreviated adj) is a describing word, the main syntactic role of which is to qualify a noun or noun phrase, giving more information about the object signified.

Adjectives are one of the English parts of speech, although they were historically classed together with the nouns.[2] Certain words that were traditionally considered to be adjectives, including the, this, my, etc., are today usually classed separately, as determiners.

Types of Use

A given occurrence of an adjective can generally be classified into one of three kinds of use:

Attributive adjectives are part of the noun phrase headed by the noun they modify; for example, happy is an attributive adjective in “happy people”. In some languages, attributive adjectives precede their nouns; in others, they follow their nouns; and in yet others, it depends on the adjective, or on the exact relationship of the adjective to the noun. In English, attributive adjectives usually precede their nouns in simple phrases, but often follow their nouns when the adjective is modified or qualified by a phrase acting as an adverb. For example: “I saw three happy kids”, and “I saw three kids happy enough to jump up and down with glee.” See also Postpositive adjective.

Predicative adjectives are linked via a copula or other linking mechanism to the noun or pronoun they modify; for example, happy is a predicate adjective in “they are happy” and in “that made me happy.”

(See also: Predicative expression, Subject complement.)

Nominal adjectives act almost as nouns. One way this can happen is if a noun is elided and an attributive adjective is left behind. In the sentence, “I read two books to them; he preferred the sad book, but she preferred the happy”, happy is a nominal adjective, short for “happy one” or “happy book”. Another way this can happen is in phrases like “out with the old, in with the new”, where “the old” means, “that which is old” or “all that is old”, and similarly with “the new”. In such cases, the adjective functions may function as a mass noun (as in the preceding example). In English, it may also function as a plural count noun denoting a collective group, as in “The meek shall inherit the Earth”, where “the meek” means “those who are meek” or “all who are meek”

ADVERB

An adverb is a word that modifies a verb, adjective, another adverb, determiner, clause, preposition, or sentence. Adverbs typically express manner, place, time, frequency, degree, level of certainty, etc., answering questions such as how?, in what way?, when?, where?, and to what extent?. This function is called the adverbial function, and may be realized by single words (adverbs) or by multi- word expressions (adverbial phrases and adverbial clauses).

Adverbs are traditionally regarded as one of the parts of speech. However, modern linguists note that the term “adverb” has come to be used as a kind of “catch-all” category, used to classify words with various different types of syntactic behavior, not necessarily having much in common except that they do not fit into any of the other available categories (noun, adjective, preposition, etc.)

Functions

The English word adverb derives (through French) from Latin adverbium, from ad- (“to”), verbum (“word”, “verb”), and the nominal suffix -ium. The term implies that the principal function of adverbs is to act as modifiers of verbs or verb phrases.[1] An adverb used in this way may provide information about the manner, place, time, frequency, certainty, or other circumstances of the activity denoted by the verb or verb phrase. Some examples:

She sang loudly (loudly modifies the verb sang, indicating the manner of singing) We left it here (here modifies the verb phrase left it, indicating place)

I worked yesterday (yesterday modifies the verb worked, indicating time)

You often make mistakes (often modifies the verb phrase make mistakes, indicating frequency)

He undoubtedly did it (undoubtedly modifies the verb phrase did it, indicating certainty)

Adverbs can also be used as modifiers of adjectives, and of other adverbs, often to indicate degree. Examples:

You are quite right (the adverb quite modifies the adjective right)

She sang very loudly (the adverb very modifies another adverb – loudly)

They can also modify noun phrases, prepositional phrases,[1] or whole clauses or sentences, as in the following examples:

I bought only the fruit (only modifies the noun phrase the fruit)

She drove us almost to the station (almost modifies the prepositional phrase to the station)

Certainly we need to act (certainly modifies the sentence as a whole) Adverbs are thus seen to perform a wide range of modifying functions. The major exception is the function of modifier of nouns, which is performed instead by adjectives (compare she sang loudly with her loud singing disturbed me; here the verb sang is modified by the adverb loudly, whereas the noun singing is modified by the adjective loud). However, as seen above, adverbs may modify noun phrases, and so the two functions may sometimes be superficially very similar: Even camels need to drink Even numbers are divisible by two

The word even in the first sentence is an adverb, since it is an “external” modifier, modifying camels as a noun phrase (compare even these camels

…), whereas the word even in the second sentence is an adjective, since it is an “internal” modifier, modifying numbers as a noun (compare these even numbers …). It is nonetheless possible for certain adverbs to modify a noun; in English the adverb follows the noun in such cases,[1] as in:

The people here are friendly

There is a shortage internationally of protein for animal feeds

Adverbs can sometimes be used as predicative expressions; in English this applies especially to adverbs of location:

Your seat is there.

When the function of an adverb is performed by an expression consisting of more than one word, it is called an adverbial phrase or adverbial clause, or simply an adverbial.

REVIEW READING STRATEGIES

Reading strategies

There are a variety of strategies used to teach reading. Strategies vary according to the challenges like new concepts, unfamiliar vocabulary, long and complex sentences, etc. trying to deal with all of these challenges at the same time may be unrealistic. Then again strategies should fit to the ability, aptitude and age level of the learner. Some of the strategies teachers use are: reading aloud, group work, and more reading exercises. Reciprocal teaching

In the 1980s Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar and Ann L. Brown developed a technique called reciprocal teaching that taught students to predict, summarize, clarify, and ask questions for sections of a text. The use of strategies like summarizing after each paragraph have come to be seen as effective strategies for building students’ comprehension. The idea is that students will develop stronger reading comprehension skills on their own if the teacher gives them explicit mental tools for unpacking text.

Instructional conversations

“Instructional conversations”, or comprehension through discussion, create higher-level thinking opportunities for students by promoting critical and aesthetic thinking about the text. According to Vivian Thayer, class discussions help students to generate ideas and new questions. (Goldenberg, p. 317). Dr. Neil Postman has said, “All our knowledge results from questions, which is another way of saying that question- asking is our most important intellectual tool”[citation needed] (Response to Intervention). There are several types of questions that a teacher should focus on: remembering; testing understanding; application or solving; invite synthesis or creating; and evaluation and judging. Teachers should model these types of questions through “think-alouds” before, during, and after reading a text. When a student can relate a passage to an experience, another book, or other facts about the world, they are “making a connection.” Making connections help students understand the author’s purpose and fiction or non- fiction story.

Text factors

There are factors, that once discerned, make it easier for the reader to understand the written text. One is the genre, like folktales, historical fiction, biographies or poetry. Each genre has its own characteristics for text structure, that once understood help the reader comprehend it. A story is composed of a plot, characters, setting, point of view, and theme. Informational books provide real world knowledge for students and have unique features such as: headings, maps, vocabulary, and an index. Poems are written in different forms and the most commonly used are: rhymed verse, haikus, free verse, and narratives. Poetry uses devices such as: alliteration, repetition, rhyme, metaphors, and similes. “When children are familiar with genres, organizational patterns, and text features in books they’re reading, they’re better able to create those text factors in their own writing.” Another one is arranging the text per perceptual span and the text display favorable to the age level of the reader.

Non-Verbal Imagery

Media that utilizes schema to make connections either planned or not, more commonly used within context such as: a passage, an experience, or one’s imagination. Some notable examples are emojis, emoticons, cropped and uncropped images, and recently Imojis which are humorous, cropped images that are used to elicit humor and comprehension.

Visualization

Visualization is a “mental image” created in a person’s mind while reading text, which “brings words to life” and helps improve reading comprehension. Asking sensory questions will help students become better visualizers. Students can practice visualizing by imagining what they “see, hear, smell, taste, or feel” when they are reading a page of a picture book aloud, but not yet shown the picture. They can share their visualizations, then check their level of detail against the illustrations.

Partner reading

Partner reading is a strategy created for pairs. The teacher chooses two appropriate books for the students’ to read. First they must read their own book. Once they have completed this, they are given the opportunity to write down their own comprehensive questions for their partner. The students swap books, read them out loud to one another and ask one another questions about the book they read.

This strategy:

Provides a model of fluent reading and helps students learn decoding skills by offering positive feedback.

Provides direct opportunities for a teacher to circulate in the class, observe students, and offer individual remediation.

Multiple reading strategies

There are a wide range of reading strategies suggested by reading programs and educators. Effective reading strategies may differ for second language learners, as opposed to native speakers. The National Reading Panel identified positive effects only for a subset, particularly summarizing, asking questions, answering questions, comprehension monitoring, graphic organizers, and cooperative learning. The Panel also emphasized that a combination of strategies, as used in Reciprocal Teaching, can be effective. The use of effective comprehension strategies that provide specific instructions for developing and retaining comprehension skills, with intermittent feedback, has been found to improve reading comprehension across all ages, specifically those affected by mental disabilities.

Reading different types of texts requires the use of different reading strategies and approaches. Making reading an active, observable process can be very beneficial to struggling readers. A good reader interacts with the text in order to develop an understanding of the information before them. Some good reader strategies are predicting, connecting, inferring, summarizing, analyzing and critiquing. There are many resources and activities educators and instructors of reading can use to help with reading strategies in specific content areas and disciplines. Some examples are graphic organizers, talking to the text, anticipation guides, double entry journals, interactive reading and note taking guides, chunking, and summarizing.[citation needed]

The use of effective comprehension strategies is highly important when learning to improve reading comprehension. These strategies provide specific instructions for developing and retaining comprehension skills across all ages. Apply methods to attain an overt phonemic awareness with intermittent practice has been found to improve reading in early ages, specifically those affected by mental disabilities.

Comprehension Strategies

Research studies on reading and comprehension have shown that highly proficient readers utilize a number of different strategies to comprehend various types of texts, strategies that can also be used by less proficient readers in order to improve their comprehension.

Making Inferences: In everyday terms we refer to this as ―reading between the lines‖. It involves connecting various parts of texts that aren‘t directly

linked in order to form a sensible conclusion. A form of assumption, the reader speculates what connections lie within the texts.

Planning and Monitoring: This strategy centers around the reader‘s mental awareness and their ability to control their comprehension by way of awareness. By previewing text (via outlines, table of contents, etc.) one can establish a goal for reading-―what do I need to get out of this‖? Readers use context clues and other evaluation strategies to clarify texts and ideas, and thus monitoring their level of understanding.

Asking Questions: To solidify one‘s understanding of passages of texts readers inquire and develop their own opinion of the author‘s writing, character motivations, relationships, etc. This strategy involves allowing oneself to be completely objective in order to find various meanings within the text.

Determining Importance:

Pinpointing the important ideas and messages within the text. Readers are taught to identify direct and indirect ideas and to summarize the relevance of each.

Visualizing: With this sensory-driven strategy readers form mental and visual images of the contents of text. Being able to connect visually allows for a better understanding with the text through emotional responses.

Synthesizing: This method involves marrying multiple ideas from various texts in order to draw conclusions and make comparisons across different texts; with the reader‘s goal being to understand how they all fit together.

Making Connections: A cognitive approach also referred to as ―reading beyond the lines‖, which involves (A) finding a personal connection to reading, such as personal experience, previously read texts, etc. to help establish a deeper understanding of the context of the text, or (B) thinking about implications that have no immediate connection with the theme of the text.

Assessment

There are informal and formal assessments to monitor an individual’s comprehension ability and use of comprehension strategies.Informal assessments are generally through observation and the use of tools, like story boards, word sorts, and interactive writing. Many teachers use Formative assessments to determine if a student has mastered content of the lesson. Formative assessments can be verbal as in a Think-Pair-Share or Partner Share. Formative Assessments can also be Ticket out the door or digital summarizers. Formal assessments are district or state assessments that evaluates all students on important skills and concepts. Summative assessments are typically assessments given at the end of a unit to measure a student’s learning.

TEXT STRUCTURE

Structured text

Structured text, abbreviated as ST or STX, is one of the five languages supported by the IEC 61131-3 standard, designed for programmable logic controllers (PLCs).[1] It is a high level language that is block structured and syntactically resembles Pascal, on which it is based. All of the languages share IEC61131 Common Elements. The variables and function calls are defined by the common elements so different languages within the IEC 61131-3 standard can be used in the same program.

TEXT ANALYSIS (CONTENT ANALYSIS)

Content analysis is a research method for studying documents and communication artifacts, which might be texts of various formats, pictures,

audio or video. Social scientists use content analysis to examine patterns in communication in a replicable and systematic manner.[1] One of the key advantages of using content analysis to analyse social phenomena is its non-invasive nature, in contrast to simulating social experiences or collecting survey answers.

Practices and philosophies of content analysis vary between academic disciplines. They all involve systematic reading or observation of texts or artifacts which are assigned labels (sometimes called codes) to indicate the presence of interesting, meaningful pieces of content.[2][3] By systematically labeling the content of a set of texts, researchers can analyse patterns of content quantitatively using statistical methods, or use qualitative methods to analyse meanings of content within texts.

Computers are increasingly used in content analysis to automate the labeling (or coding) of documents. Simple computational techniques can provide descriptive data such as word frequencies and document lengths. Machine learning classifiers can greatly increase the number of texts that can be labeled, but the scientific utility of doing so is a matter of debate.

Goals

Content analysis is best understood as a broad family of techniques. Effective researchers choose techniques that best help them answer their substantive questions. That said, according to Klaus Krippendorff, six questions must be addressed in every content analysis:[4]

Which data are analyzed? How are the data defined?

From what population are data drawn? What is the relevant context?

What are the boundaries of the analysis? What is to be measured?

The simplest and most objective form of content analysis considers unambiguous characteristics of the text such as word frequencies, the page area taken by a newspaper column, or the duration of a radio or television program. Analysis of simple word frequencies is limited because the meaning of a word depends on surrounding text. Keyword In Context routines address this by placing words in their textual context. This helps resolve ambiguities such as those introduced by synonyms and homonyms.

A further step in analysis is the distinction between dictionary-based (quantitative) approaches and qualitative approaches. Dictionary-based

approaches set up a list of categories derived from the frequency list of words and control the distribution of words and their respective categories over the texts. While methods in quantitative content analysis in this way transform observations of found categories into quantitative statistical data, the qualitative content analysis focuses more on the intentionality and its implications. There are strong parallels between qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis.

READING TEXT AND ASSIGNMENT

Reading comprehension is the ability to process text, understand its meaning, and to integrate with what the reader already knows.[1][2] Fundamental skills required in efficient reading comprehension are knowing meaning of words, ability to understand meaning of a word from discourse context, ability to follow organization of passage and to identify antecedents and references in it, ability to draw inferences from a passage about its contents, ability to identify the main thought of a passage, ability to answer questions answered in a passage, ability to recognize the literary devices or propositional structures used in a passage and determine its tone, to understand the situational mood (agents, objects, temporal and spatial reference points, casual and intentional inflections, etc.) conveyed for assertions, questioning, commanding, refraining etc. and finally ability to determine writer’s purpose, intent and point of view, and draw inferences about the writer (discourse-semantics).[3][4]

An individual’s ability to comprehend text is influenced by their skills and their ability to process information. If word recognition is difficult, students use too much of their processing capacity to read individual words, which interferes with their ability to comprehend what is read. There are a number of reading strategies to improve reading comprehension and inferences, including improving one’s vocabulary, critical text analysis (intertextuality, actual events vs. narration of events, etc.) and practicing deep reading.

Homework, or a homework assignment, is a set of tasks assigned to students by their teachers to be completed outside the class. Common homework assignments may include required reading, a writing or typing project, mathematical exercises to be completed, information to be reviewed before a test, or other skills to be practiced.

The effect of homework is debated. Generally speaking, homework does not improve academic performance among children[citation needed] and may improve academic skills among older students, especially lower-

achieving students. Homework also creates stress for students and their parents and reduces the amount of time that students could spend outdoors, exercising, playing, working, sleeping, or in other activities.

Purposes

The basic objectives of assigning homework to students are the same as schooling in general: to increase the knowledge and improve the abilities and skills of the students, to prepare them for upcoming (or complex or difficult) lessons, to extend what they know by having them apply it to new situations, or to integrate their abilities by applying different skills to a single task. Homework also provides an opportunity for parents to participate in their children’s education. Homework is designed to reinforce what students have already learned.

LISTENING STRATEGIES

Listening strategies: The process of teaching hard of hearing persons common and alternative strategies when listening with or without amplification to improve their communication

Listening is the one skill that you use the most in everyday life. Listening comprehension is the basis for your speaking, writing and reading skills. To train your listening skills, it is important to listen actively, which means to actively pay attention to what you are listening to. Make it a habit to listen to audio books, podcasts, news, songs, etc. and to watch videos and films in the foreign language. You should know that there are different types of listening:

Listening for gist: you listen in order to understand the main idea of the text. Listening for specific information: you want to find out specific details, for example key words.

Listening for detailed understanding: you want to understand all the information the text provides.

Before you listen to a text, you should be aware of these different types. You will have to decide what your purpose is. Becoming aware of this fact will help you to both focus on the important points and reach your goal.

Suggestions for improving your listening skills Before you listen

- Think about the topic of the text you are going to listen to. What do you already know about it? What could possibly be the content of the text? Which words come to mind that you already know? Which words would you want to look up?

- If you have to do a task on the listening text, check whether you have understood the task correctly.

- Think about what type of text you are going to listen to. What do you know about this type of text?

- Relax and make yourself ready to pay attention to the listening text. While you are listening

- It is not necessary to understand every single word. Try to ignore those words that you think are less important anyway.

- If there are words or issues that you don’t understand, use your general knowledge as well as the context to find out the meaning.

- If you still don’t understand something, use a dictionary to look up the words or ask someone else for help.

- Focus on key words and facts.

- Take notes to support your memory.

- Intonation and stress of the speakers can help you to understand what you hear. Try to think ahead. What might happen next? What might the speakers say, which words might they use?

- After listening, Think about the text again. Have you understood the main points?

- Remember the speculations you made before you listened. Did they come true? Review your notes.

- Check whether you have completed your task correctly.

- Have you had any problems while listening? Do you have any problems now to complete your task? Identify your problems and ask someone for help.

- Listen again to difficult passages. LISTENING CONVERSATION

- Listening Lessons have straight forward questions and answers but with longer dialogs. If you listen, you should be able to clearly hear the answer from the audio file.

- If you are still uncertain about the dialog, you can click on “Show Conversation Dialog” to see the text. I recommend to not view the Conversation Dialog until you really try to listen without reading.

· https://www.talkenglish.com/listening/lessonlisten.aspx?ALID=100

Asic And Daily Conversaton

Do you feel nervous and forgetful when talking with English speakers?

When I was studying Spanish, basic conversational skills were the hardest thing for me to learn.

Whenever someone asked me a question, I would freeze up and forget how to talk.

When it came time to hold a Spanish conversation, I would suddenly forget everything I studied. That‘s when I realized that I had not been practicing my conversational skills.

I spent six years studying the language at high school and college, but I never got the opportunity chat with actual Spanish speakers.

The mistake that a lot of students, including myself, make when learning a foreign language is forgetting to practice real-world conversational skills.

Instead, we spend our time memorizing vocabulary words and doing workbook activities. And while these exercises are also important, they don‘t teach us how to speak naturally.

What You Need to Hold a Basic English Conversation

Being able to have a basic English conversation isn‘t hard—you just need to know how to express yourself and start with brief, simple conversations.

To hold a basic conversation, you need to be able to:

Introduce yourself and share some personal information. Talk about your needs and expectations.

Make future plans.

Talk about your career and your educational background.

Hold simple conversations with people you encounter in day-to-day activities, like shopping, going to the bank or going to the doctor’s office.

Greetings, Congratulation, Parting, Excuses, Thanks

Do you want to say more than ―Hi‖ and ―How are you?‖

And would you like to sound like a native English speaker now (instead of waiting until you reach the advanced level)?

You‘re in the right place!

Below are 30 basic phrases that people use every day. They are useful phrases that‘ll also help your knowledge of English grow.

First, let’s look at a few ideas for how to learn these new phrases.

As you read each phrase below for the first time, say it aloud four times. Yes, four times! (They‘re short phrases.)

Then, print this list of phrases.

If you have a conversation partner, ask your exchange partner to say the phrases while you record them on a smartphone, computer or recording device. That way you can listen to the recording and practice the

pronunciation by yourself at home.

Then, choose two phrases each day to focus on. Here’s what you could do every

day to learn each phrase:

Picture a situation in your mind where you could use the phrase. Imagine the other people in the scene and what they‘re saying. See yourself saying the phrase. Listen/look for the phrase while you watch TV, listen to the radio,

read blogs, etc. Then, use the phrase in casual writing. Write a tweet (on Twitter), a Facebook post or an email to a friend.

Finally, use the phrase in 2-5 real conversations.

These first eight phrases can be used in many different situations.

- Thanks so much.

This is a simple sentence you can use to thank someone. To add detail, say:

Thanks so much + for + [noun] / [-ing verb]. For example:

Thanks so much for the birthday money. Thanks so much for driving me home.

2. I really appreciate…

You can also use this phrase to thank someone. For example, you might say: I really appreciate your help.

Or you can combine #1 and #2:

Thanks so much for cooking dinner. I really appreciate it. Thanks so much. I really appreciate you cooking dinner.

3. Excuse me.

When you need to get through but there‘s someone blocking your way, say ―Excuse me.‖

You can also say this phrase to politely get someone’s attention. For example:

Excuse me sir, you dropped your wallet. Excuse me, do you know what time it is?

4. I’m sorry.

Use this phrase to apologize, whether for something big or small. Use ―for‖ to give more detail. For example:

I‘m sorry for being so late.

I‘m sorry for the mess. I wasn‘t expecting anyone today.

You can use ―really‖ to show you‘re very sorry for something: I‘m really sorry I didn‘t invite you to the party.

5. What do you think?

When you want to hear someone‘s opinion on a topic, use this question. I‘m not sure if we should paint the room yellow or blue. What do you think?

6. How does that sound?

If you suggest an idea or plan, use this phrase to find out what others think. We could have dinner at 6, and then go to a movie. How does that sound?

Let‘s hire a band to play music, and Brent can photograph the event. How does that sound?

7. That sounds great.

If you like an idea, you can respond to #6 with this phrase. ―Great‖ can be replaced with any synonym, such as ―awesome,‖ ―perfect,‖ ―excellent‖ or

―fantastic.‖

A: My mom is baking cookies this afternoon. We could go to my house and eat some. How does that sound?

B: That sounds fantastic!

8. (Oh) never mind.

Let‘s say someone doesn‘t understand an idea you‘re trying to explain. If you‘ve explained it over and over and want to stop, just say ―oh, never mind.‖ You can now talk about something else!

You can also use ―never mind‖ to mean ―it doesn‘t matter‖ or ―just forget it.‖ In these situations, say it with a smile and positive tone, though. Otherwise, when you say this phrase slowly with a falling low tone, it can mean you‘re bothered or upset.

A: Are you going to the grocery store today?

B: No, I‘m not. But why—do you need something? A: Oh, never mind. It‘s okay, I‘ll go tomorrow.

Phrases for Learning English

As an English learner, you‘ll need to tell others that English is not your first language. You‘ll also need to ask native speakers to repeat phrases and words or to speak slower. The following phrases will be useful for this.

9. I’m learning English.

This simple phrase tells people that English is not your native language. If you‘re a total beginner, add ―just started‖ after I: ―I just started learning English.‖

My name is Sophie and I‘m learning English.

10. I don’t understand.

Use this phrase when you don‘t understand what someone means.

Sorry, I don‘t understand. The U.S. Electoral College seems very confusing!

11. Could you repeat that please?

If you‘d like someone to say a word, question or phrase again, use this question. Since ―to repeat‖ means ―to say again,‖ you can also ask, ―Could you say that again please?‖

We can say ―please‖ either at the end of the question or right after ―you,‖ like this:

Could you please repeat that? Could you repeat that please?

12. Could you please talk slower?

Native speakers can talk very fast. Fast English is hard to understand! This is an easy way to ask someone to speak more slowly.

Note: This phrase is not grammatically correct. However, it‘s used often in everyday (casual) speech. The grammatically correct question would be,

―Could you please talk more slowly?‖

That‘s because ―slowly‖ is an adverb, so it describes verbs (like ―talk‖).

―Slower‖ is a comparative adjective, which means it should be used to describe nouns (people, places or thing), not verbs. (For example: My car is slower than yours.)

A: You can give us a call any weekday from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. at five five five, two five zero eight, extension three three—

B: I‘m sorry, could you please talk slower?

13. Thank you. That helps a lot.

After someone starts speaking more slowly for you, thank them with this phrase. You can use it in many other situations, too.

A: Ben, could you please make the font bigger? It‘s hard for me to read the

words. B: Sure! I‘ll change it from size 10 to 16. How‘s this? A: Thank you. That helps a lot.

14. What does ~ mean?

When you hear or see a new word, use this phrase to ask what it means.

A: What does ―font‖ mean?

B: It‘s the style of letters, numbers and punctuation marks when you type. A common font in the USA is Times New Roman.

15. How do you spell that?

English spelling can be tricky, so make sure to learn this question. You could also ask someone, ―Could you spell that for me?‖

A: My name is Robbertah Handkerchief. B: How do you spell that?

16. What do you mean?

When you understand the words one by one, but not what they mean together, use this question. You can ask it whenever you‘re confused about what someone is telling you.

A: The Smiths do have a really nice house, but the grass is always greener on the other side.

B: What do you mean?

A: I mean that if we had the Smith‘s house, we probably wouldn‘t be happier. We always think other people have better lives than us, but other people have problems too.

Phrases for Introducing Yourself and Making Friends

Here are some phrases for introducing yourself when you meet new people, and questions to learn more about them.

17. Hi! I’m [Name]. (And you?)

Here‘s an informal greeting you can use when you meet new friends. If the person doesn‘t tell you their name, you can ask ―And you?‖ or ―And what‘s your name?‖

Hi! I‘m Rebecca. And you?

18. Nice to meet you.

After you learn each other‘s names, it‘s polite to say this phrase.

A: Hi Rebecca, I‘m Chad. B: Nice to meet you, Chad. A: Nice to meet you too.

19. Where are you from?

Ask this question to find out which country someone is from. You answer this question with ―I‘m from ~.‖

Can you answer this question in English? Say both the question and answer aloud right now. (Four times, remember?)

A: Nice to meet you, Sergio. So, where are you from? B: I‘m from Spain.

20. What do you do?

Most adults ask each other this question when they meet. It means what do you do for a living (what is your job).

I think this question is boring, so I ask other questions. But many people will probably ask you this, so it‘s important to know what it means.

A: What do you do, Cathleen?

B: I work at the university as a financial specialist.

21. What do you like to do (in your free time)?

Instead of asking for someone‘s job title, I prefer to ask what they enjoy doing. The responses (answers) are usually much more interesting!

A: So Cathleen, what do you like to do in your free time?

B: I love to read and to garden. I picked two buckets of tomatoes last week!

22. What’s your phone number?

If you want to keep in contact with someone you just met, ask this question to find out their phone number. You can replace ―phone number‖ with

―email address‖ if you want to know their email address.

You might also hear people use the more casual ―Can I get your ~?,‖ as in,

―Can I get your phone number?‖

It would be great to meet up again sometime. What‘s your phone number?

23. Do you have Facebook?

Many people keep in touch (contact) through Facebook. Use this question to find out if someone has a Facebook account. You might also ask, ―Are you on Facebook?‖

Let‘s keep in touch! Do you have Facebook? Phrases for at Work

Finally, here are seven basic phrases you might use at a job.

24. How can I help you?

If you work in customer service, you‘ll use this phrase a lot. It‘s also a common phrase when answering the phone.

[On the phone]: Hello, this is Rebecca speaking. How can I help you?

25. I’ll be with you in a moment.

When someone wants to see you, use this phrase if you need a minute to finish something first. If a client is waiting at a store, you can also use this phrase to show that their turn is next.

You can replace ―moment‖ with ―minute‖: ―I‘ll be with you in (just) a minute.‖ Another common phrase for this situation is ―I‘ll be right with you.‖

Good morning! I‘ll be with you in a moment.

26. What time is our meeting?

You can use this question‘s structure to ask the time of any event: ―What time is [event]?‖

If you want to ask about a meeting on a certain day, add ―on [day].‖ For example, ―What time is our meeting on Thursday?‖

What time is our meeting on Wednesday?

27. Please call me (back) at…

When you want someone to call you or to call you back (to return your call), use this phrase to give your phone number.

Hi, this is Cathleen from the financial office.

I‘m wondering if you found those missing receipts. Please call me back at 555-5555. Thanks!

28. (Oh really?) Actually, I thought…

When you disagree with someone, ―Actually, I thought…‖ will make you sound kinder and more polite than saying ―No‖ or ―You‘re wrong.‖ This phrase is useful when you have a different idea than someone else.

A: So Sam‘s coming in tonight at 8, right?

B: Actually, I thought he wasn‘t working at all this week. A: Oh, ok. I‘ll have to look at the schedule again.

29. Actually, I [verb]…

Just like in #28, you can use ―actually, I…‖ with many different verbs:

―heard,‖ ―learned,‖ ―am,‖ ―can,‖ ―can‘t,‖ etc. You should use it for the same situation as above: when you have a different idea than someone else.

A: Did you finish the reports?

B: Actually, I am running a bit behind, but they‘ll be done by noon!

C: When you type, always put two spaces between sentences. D: Actually, I learned to put a single space between sentences.

30. I’m (just) about to [verb]…

When you‘re going to start something very soon, you‘re ―just about to‖ do something.

I‘m just about to send those faxes.

I‘m about to go and pick up some coffee. Do you want anything?

DISCUSSION and CONVERSATION DRILLS

A discussion group is a group of individuals with similar interest who gather either formally or informally to bring up ideas, solve problems or give comments. The major approaches are in person, via conference call or website.[1] People respond comments and post forum in established mailing list, news group or IRC.[2] Other group members could choose to respond by posting text or image.

Small group of professionals or students formally or informally negotiate about an academic topic within certain fields. This implementation could be seen as an investigation or research based on various academic levels. For instance, “one hundred eighty college-level psychology students” breakdown into different groups to participate in giving an orderly arrangement of preferred events.[15] Nevertheless, discussion groups could support professional services and hold events to a range of demographics; another distinguished example is from “The London Biological Mass Spectrometry Discussion Group”, which sustainably operates by gathering “technicians, clinicians, academics, industrialists and students” to exchange ideas on an academic level.[16] It attributes to the development of participants’ cognitive, critical thinking,

and analytical skills.

SPEECH, PRESENTATION and GIVING TALK

Speech production (English) visualized by Real-time MRI Part of a series on Linguistics OutlineHistoryIndex Subfields[hide] Acquisition Anthropological Applied Computational Discourse analysis Forensic Historical Lexicography Morphology Neurolinguistics Philosophy of language Phonetics Phonology Pragmatics Psycholinguistics Semantics Sociolinguistics Syntax Grammatical Theories[hide] Cognitive Constraint-based Dependency Functional Generative Stochastic Topics[hide] Descriptivism Etymology Internet linguistics LGBT linguistics Linguistic anthropology Origin of language Origin of speech Orthography Prescriptivism Second-language acquisition Structuralism Linguistics portal vte

Speech is human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of a limited set of perfectly articulated and individualized vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are the same word, e.g., “role” or “hotel”), and using those words in their semantic character as words in the lexicon of a language according to the syntactic constraints that govern lexical words’ function in a sentence. In speaking, speakers perform many different intentional speech acts, e.g., informing, declaring, asking, persuading, directing, and can use enunciation, intonation, degrees of loudness, tempo, and other non- representational or paralinguistic aspects of vocalization to convey meaning. In their speech speakers also unintentionally communicate many aspects of their social position such as sex, age, place of origin (through accent), physical states (alertness and sleepiness, vigor or weakness, health or illness), psychic states (emotions or moods), physico-psychic states (sobriety or drunkenness, normal consciousness and trance states), education or experience, and the like.

Although people ordinarily use speech in dealing with other persons (or animals), when people swear they do not always mean to communicate anything to anyone, and sometimes in expressing urgent emotions or desires they use speech as a quasi-magical cause, as when they encourage a player in a game to do or warn them not to do something. There are also many situations in which people engage in solitary speech. People talk to themselves sometimes in acts that are a development of what some psychologists (e.g., Lev Vygotsky) have maintained is the use in thinking of silent speech in an interior monologue to vivify and organize cognition, sometimes in the momentary adoption of a dual persona as self addressing self as though addressing another person. Solo speech can be used to memorize or to test one’s memorization of things, and in prayer or in meditation (e.g., the use of a mantra).

Researchers study many different aspects of speech: speech production and speech perception of the sounds used in a language, speech repetition, speech errors, the ability to map heard spoken words onto the vocalizations needed to recreate them, which plays a key role in