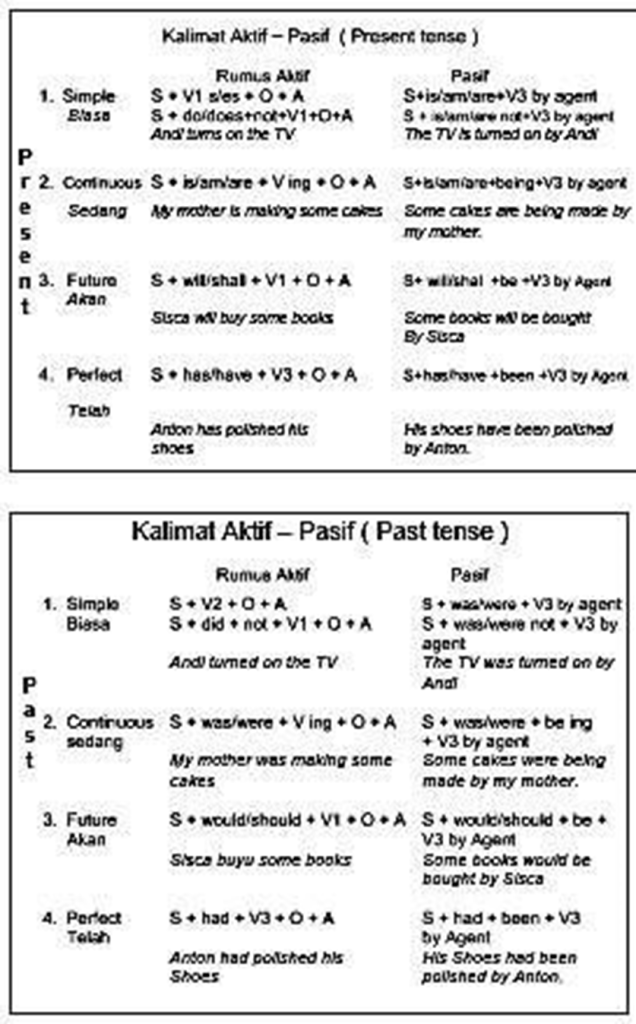

KALIMAT PASIF

CLAUSES

In language, a phrase is the smallest grammatical unit that can express an incomplete proposition.[1] A typical clause consists of a subject and a predicate,[2] the latter typically a verb phrase, a verb with any objects and other modifiers. However, the subject is sometimes not said or explicit, often the case in null-subject languages if the subject is retrievable from context, but it sometimes also occurs in other languages such as English (as in imperative sentences and non-finite clauses).

A simple sentence usually consists of a single finite clause with a finite verb that is independent. More complex sentences may contain multiple clauses. Main clauses (matrix clauses, independent clauses) are those that can stand alone as a sentence. Subordinate clauses (embedded clauses, dependent clauses) are those that would be awkward or incomplete if they were alone.

In language, a phrase is the smallest grammatical unit that can express an incomplete proposition.[1] A typical clause consists of a subject and a predicate,[2] the latter typically a verb phrase, a verb with any objects and other modifiers. However, the subject is sometimes not said or explicit, often the case in null-subject languages if the subject is retrievable from context, but it sometimes also occurs in other languages such as English (as in imperative sentences and non-finite clauses).

A simple sentence usually consists of a single finite clause with a finite verb that is independent. More complex sentences may contain multiple clauses. Main clauses (matrix clauses, independent clauses) are those that can stand alone as a sentence. Subordinate clauses (embedded clauses, dependent clauses) are those that would be awkward or incomplete if they were alone.

Two major distinctions

A primary division for the discussion of clauses is the distinction between main clauses (i.e. matrix clauses, independent clauses) and subordinate clauses (i.e. embedded clauses, dependent clauses).[3] A main clause can stand alone, i.e. it can constitute a complete sentence by itself. A subordinate clause (i.e. embedded clause), in contrast, is reliant on the appearance of a main clause; it depends on the main clause and is therefore a dependent clause, whereas the main clause is an independent clause.

A second major distinction concerns the difference between finite and non-finite clauses. A finite clause contains a structurally central finite verb, whereas the structurally central word of a non-finite clause is often a non-finite verb. Traditional grammar focuses on finite clauses, the awareness of non-finite clauses having arisen much later in connection with the modern study of syntax. The discussion here also focuses on finite clauses, although some aspects of non-finite clauses are considered further below.

Argument clauses

A clause that functions as the argument of a given predicate is known as an argument clause. Argument clauses can appear as subjects, as objects, and as obliques. They can also modify a noun predicate, in which case they are known as content clauses.

- That they actually helped was really appreciated. – SV-clause functioning as the subject argument

- They mentioned that they had actually helped. – SV-clause functioning as the object argument

- What he said was ridiculous. – Wh-clause functioning as the subject argument We know what he said. – Wh-clause functioning as an object argument

- He talked about what he had said. – Wh-clause functioning as an oblique object argument

The following examples illustrate argument clauses that provide the content of a noun. Such argument clauses are content clauses:

- the claim that he was going to change it – Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause)

- the claim that he expressed – Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun

- the idea that we should alter the law – Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause)

- the idea that came up – Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun The content clauses like these in the a-sentences are arguments. Relative clauses introduced by the relative pronoun that as in the b- clauses here have an outward appearance that is closely similar to that of content clauses. The relative clauses are adjuncts, however, not arguments.

Adjunct clauses

Adjunct clauses are embedded clauses that modify an entire predicate-argument structure. All clause types (SV-, verb first, wh-) can function as adjuncts, although the stereotypical adjunct clause is SV and introduced by a subordinator (i.e. subordinate conjunction, e.g. after, because, before, when, etc.), e.g.

- Fred arrived before you did. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

- After Fred arrived, the party started. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

- Susan skipped the meal because she is fasting. – Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause

These adjunct clauses modify the entire matrix clause. Thus before you did in the first example modifies the matrix clause Fred arrived. Adjunct clauses can also modify a nominal predicate. The typical instance of this type of adjunct is a relative clause, e.g.

- We like the music that you brought. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun music

- The people who brought music were singing loudly. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun people

- They are waiting for some food that will not come. – Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun food

Predicative clauses

An embedded clause can also function as a predicative expression. That is, it can form (part of) the predicate of a greater clause.

- That was when they laughed. – Predicative SV-clause, i.e. a clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

- He became what he always wanted to be. – Predicative wh-clause, i.e. wh- clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

- These predicative clauses are functioning just like other predicative expressions,

- e.g. predicative adjectives (That was good) and predicative nominals (That was the truth). They form the matrix predicate together with the copula.

MODALS

A modal verb is a type of verb that is used to indicate modality – that is: likelihood, ability, permission, request, capacity, suggestions, order and obligation, and advice etc. They always take v1 form with them.[1] Examples include the English verbs can/could, may/might, must, will/would and shall/should. In English and other Germanic languages, modal verbs are often distinguished as a class based on certain grammatical properties.

Function

A modal auxiliary verb gives information about the function of the main

verb that it governs. Modals have a wide variety of communicative functions, but these functions can generally be related to a scale ranging from possibility (“may”) to necessity (“must”), in terms of one of the following types of modality:

epistemic modality, concerned with the theoretical possibility of propositions being true or not true (including likelihood and certainty) deontic modality, concerned with possibility and necessity in terms of freedom to act (including permission and duty)

dynamic modality,[2] which may be distinguished from deontic modality in that, with dynamic modality, the conditioning factors are internal – the subject’s own ability or willingness to act[3]

The following sentences illustrate epistemic and deontic uses of the English modal verb must:

epistemic: You must be starving. (“It is necessarily the case that you are starving.”)

deontic: You must leave now. (“You are required to leave now.”)

An ambiguous case is You must speak Spanish. The primary meaning would be the deontic meaning (“You are required to speak Spanish.”) but this may be intended epistemically (“It is surely the case that you speak Spanish.”) Epistemic

modals can be analyzed as raising verbs, while deontic modals can be analyzed as control verbs.

Epistemic usages of modals tend to develop from deontic usages.[4] For example, the inferred certainty sense of English must developed after the strong obligation sense; the probabilistic sense of should developed after the weak obligation sense; and the possibility senses of may and can developed later than the permission or ability sense. Two typical sequences of evolution of modal meanings are:

internal mental ability → internal ability → root possibility (internal or

external ability) → permission and epistemic possibility obligation →

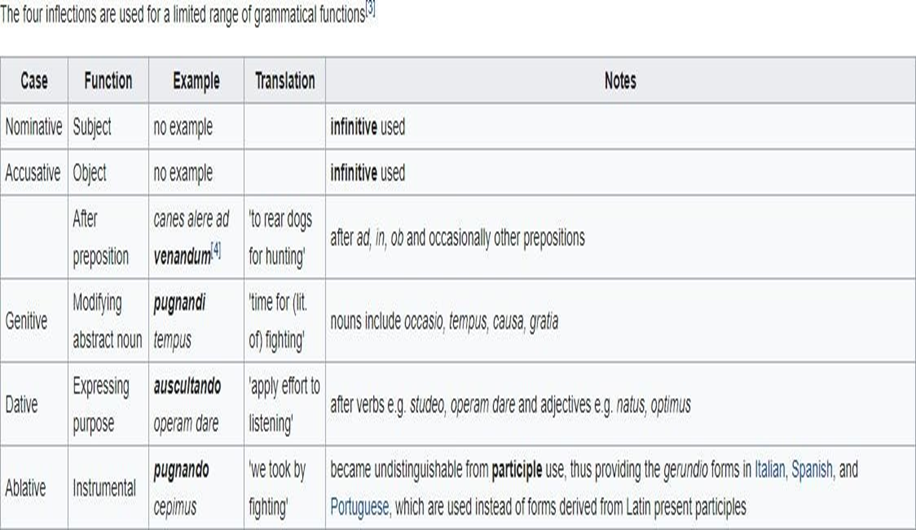

probability GERUNDS

A gerund (/ˈdʒɛrənd, -ʌnd/[1] abbreviated ger) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages, most often, but not exclusively, one that functions as a noun. In English it is a type of verbal noun, one that retains properties of a verb, such as being modifiable by an adverb and being able to take a direct object. The term “-ing form” is often used in English to refer to the gerund specifically. Traditional grammar made a distinction within -ing forms between present participles and gerunds, a distinction that is not observed in such modern, linguistically informed grammars as A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language and The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.

These functions could be fulfilled by other abstract nouns derived from verbs such as vẽnãtiõ ‘hunting’. Gerunds are distinct in two ways.

Every Latin verb can regularly form a gerund

A gerund may function syntactically in the same way as a finite verb. Typically the gerund of a finite verb may be followed by a direct object e.g. ad discernendum vocis verbis figuras ‘for discerning figures of speech’, hominem investigando opera dabo ‘I will devote effort to investigating the man’.

However, this was a rare construction. Writers generally preferred the gerundive construction e.g. res evertendae reipublicae ‘matters concerning the overthrow of the state’ (literally ‘of the state being overthrown’).

When people first wrote grammars of languages such as English, and based them on works of Latin grammar, they adopted the term gerund to label non-finite verb forms with these two properties.